America’s first case of Omicron, a heavily mutated COVID-19 variant, has been identified in California, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Wednesday afternoon.

The patient, who was fully vaccinated, returned to San Francisco from South Africa Nov. 22 before testing positive Nov. 29. The patient is now self-quarantining. So far, all close contacts have tested negative.

The first case, however inevitable it might have been, doesn’t necessarily mean the United States is about to face the worst case in Omicron, with more than double the mutations of the highly transmissible Delta variant that remains the dominant global strain.

Earlier this week, Moderna CEO Stephane Bancel warned of a “material drop” in the effectiveness of current vaccines against Omicron. But, without more data on patient cases, that could represent a doomsday scenario.

“The analogy would maybe be something similar to the flu shot,” says Dr. Ulysses Wu, Hartford HealthCare’s System Director of Infection Disease and Chief Epidemiologist, “which has some variable effectiveness every flu season. So if there is some protection, whether it’s Moderna and/or Pfizer (vaccine), it’s better than no protection.”

With so few confirmed cases of the variant first identified last month in South Africa, virologists need about two weeks to assess Omicron, which has 50 mutations. There’s also a lag, usually between a week to 12 days, between an infection and hospitalization. The first cases were mostly college students with only a mild illness — young people typically do not get severe COVID. It’s difficult to tell this early how Omicron will affect older populations and people with existing medical conditions.

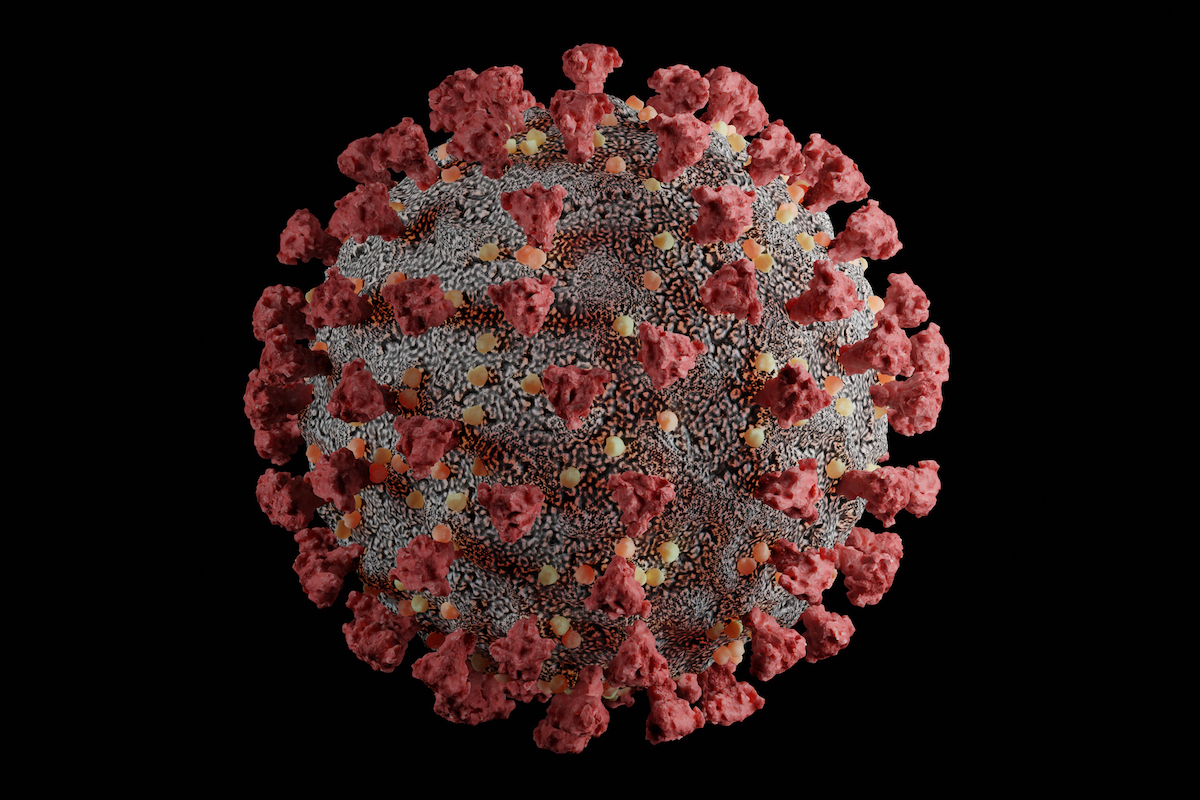

Scientists can attempt to replicate Omicron’s behavior in a laboratory by creating otherwise harmless pseudoviruses and attaching parts of Omicron to determine if, as suspected, the new variant can evade some of the immune protection built by vaccines. Omicron has an unprecedented number of mutations that affect a key part of the spike protein (see image above) used by the virus to infect host cells.

Fortunately, messenger RNA (mRNA) technology used by both the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines allows on-the-fly updates using a new variant’s genomic information. Bancel said it could take 60 to 90 days to develop a vaccine specifically for Omicron.

“That’s the beauty of this technology,” says Dr. Wu. “It can be very quickly adapted to create new vaccines. This could turn out to be a deadlier, more transmissible, worse virus. But the reality is we still have a current virus (Delta) that is really bad.”