While the nation is clamoring for more information about the new treatment approved by the Food and Drug Administration for depression, Drs. Andrew Winokur and Mirela Loftus are quietly working on the next application.

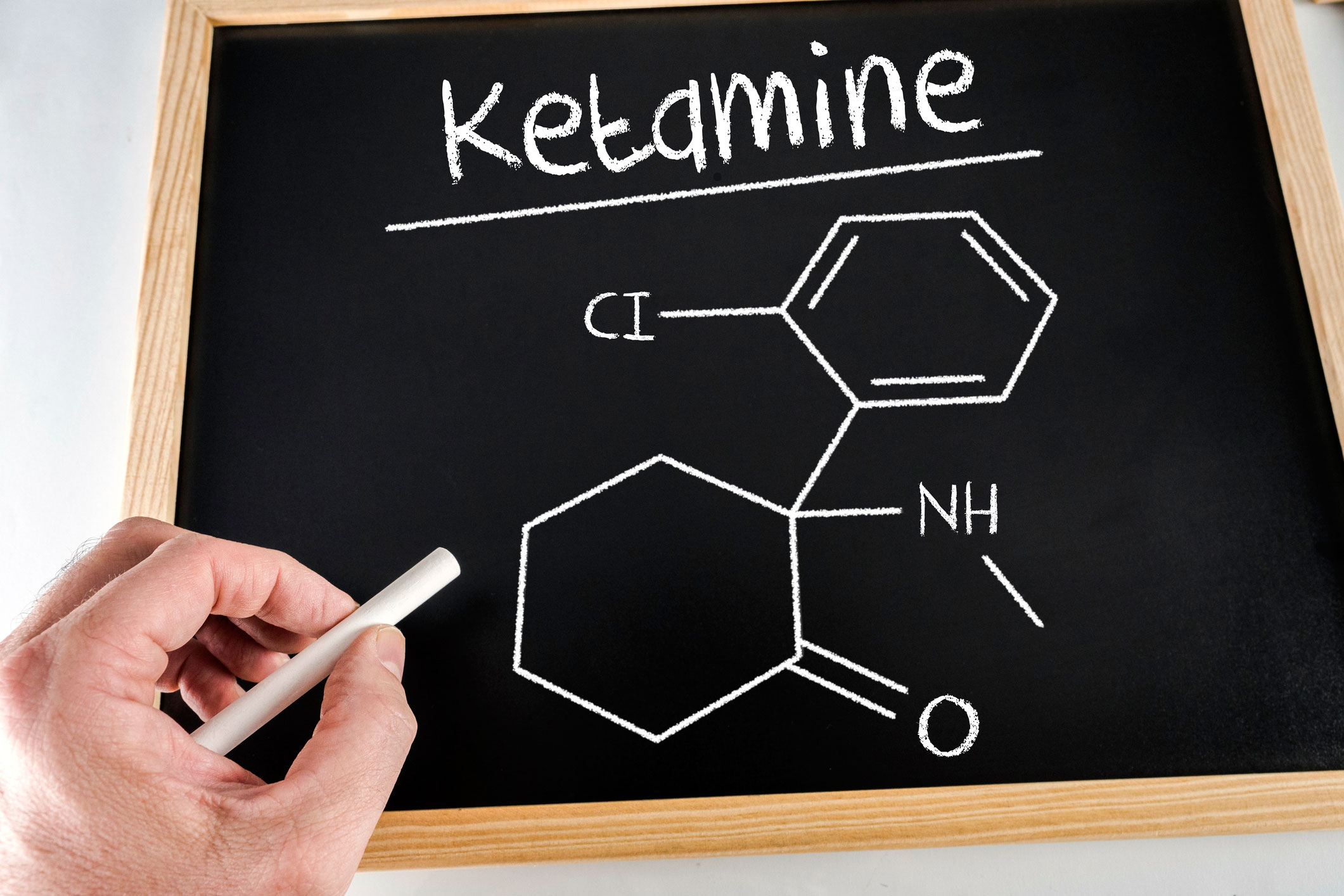

A nasal spray containing the active ingredient Esketamine — a chemical “relative” of the drug ketamine that has served as an anesthetic for decades – was approved for use against severe (treatment resistant) cases of depression in adults. Dr. Loftus, a child and adolescent psychiatrist, has been part of a research team affiliated with the Institute of Living testing various applications of the drug, marketed as Spravato, for depression.

The initial results in patients, she said, are astonishing,

“There are people who have been in our study for two or three years and every one of them has had the same story about how life-changing this is for them,” Dr. Loftus said.

Esketamine alters the chemical functioning of the brain in a manner that is different from antidepressant drugs currently on the market. Besides affecting the chemical shift in the brain that sparks depression, Esketamine works on the glutamate, affecting the synaptic plasticity. In other words, it potentially changes the connections or synapses in the brain that contribute to depression.

“The mechanism of action here is very different than any other anti-depression medication on the market now,” Dr. Loftus said.

A controlled substance, Esketamine must be administered in an approved clinic environment in which the patient is monitored for an hour or two for any adverse reaction. Such reactions, she said, can include elevated blood pressure and an altered perception of reality such as dissociation, dizziness, sleepiness or seeing double.

A variety of questions about the medication remain, however, and Dr. Loftus said researchers will continue to seek answers. For example, while there have been appropriate concerns about abuse potential related to the inappropriate use of ketamine (sometimes referred to as Special K), in carefully controlled clinical trials of Esketamine, problems with dependence or abuse have not been identified to date, although more research on this topic is needed.

“There has not been a long enough period of observation to know the answer to that,” she began. “But, why would I give a drug of abuse? It’s a completely different way of delivery and dosing than in the street.”

She is also involved in other research projects through the IOL’s Clinical Trials Unit, including one investigating the use of Esketamine in children and adolescents.

“The IOL is one of the few sites in the world using this in children and adolescents. We just recruited the second adolescent in the world for our study,” Dr. Loftus said, noting that the work is focused on children and adolescents presenting with suicidal thoughts, the most severe form of depression.

In addition, the IOL team is hoping to discover how to shorten the patient reaction time to the medication. Currently, Esketamine takes a few days to show an effect, as opposed to weeks for existing antidepressants. Further research is needed to see if there are certain conditions in which the effect would be even shorter, even just hours.

For more information about treatment for depression at the Hartford HealthCare Behavioral Health Network, click here. For learn more about the Institute of Living’s Clinical Trials Unit, click here.